Sovereign Algorithms

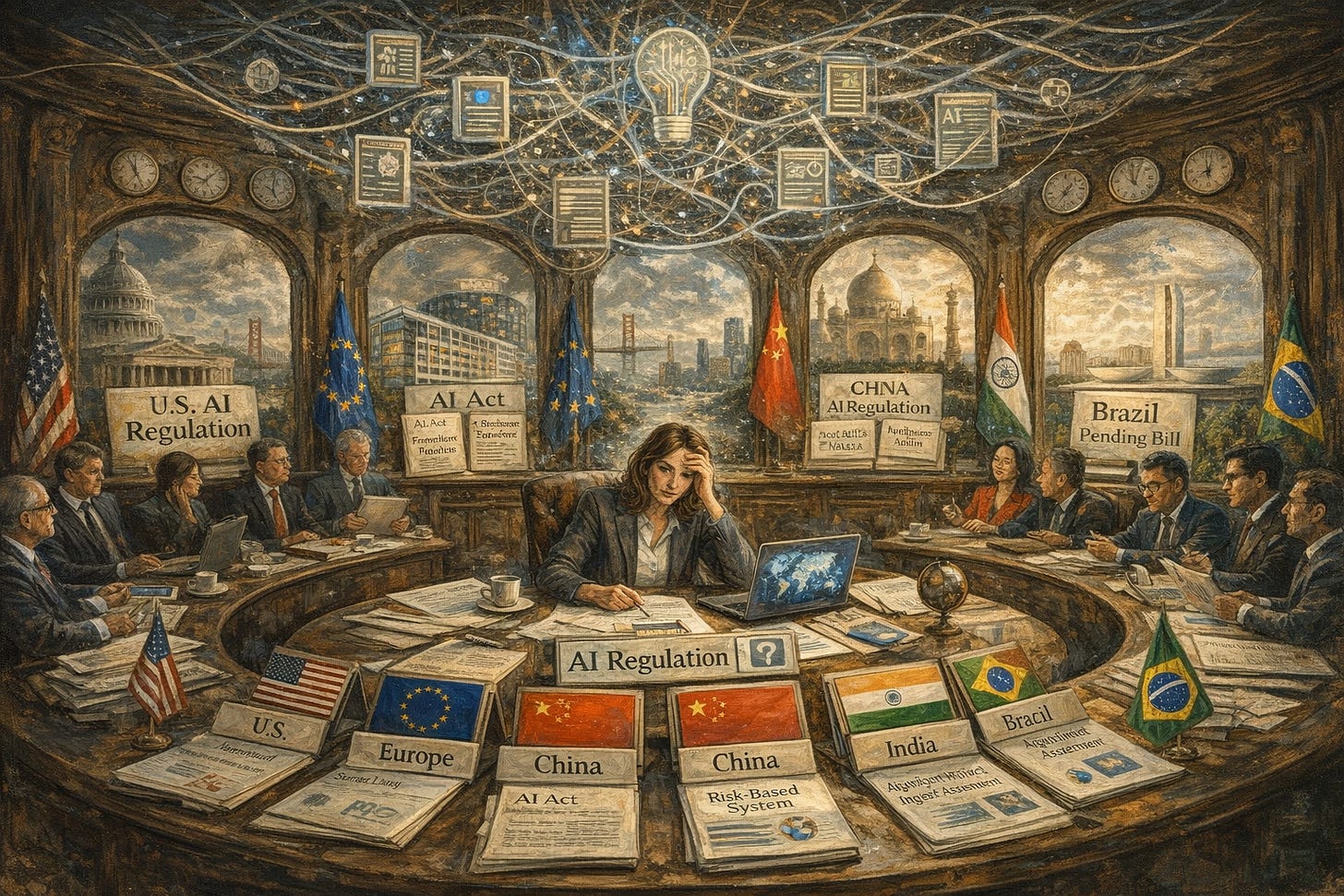

The world is regulating AI in five different directions at once. Here's what that actually means — and what to do about it.

A technology company in San Francisco builds an AI-powered hiring platform. It screens résumés, conducts video interviews through natural language processing, and generates ranked candidate lists for human recruiters. It works well. The company’s general counsel prepares for a routine global rollout.

The rollout is anything but routine.

In the United States, no comprehensive federal AI legislation exists. The company has conducted a voluntary bias audit and published a model card, but faces no pre-deployment regulatory obligation. In the European Union, the same system is classified as “high-risk” under the AI Act, triggering mandatory risk management, conformity assessment, technical documentation, human oversight capabilities, and registration in a public database — all before the system can lawfully be placed on the market. In China, the system’s algorithmic recommendation features require algorithm filing with the Cyberspace Administration, transparency about recommendation logic, and compliance with “socialist core values” — a requirement with no analogue in any Western legal system. In Brazil, pending legislation would impose fundamental-rights-based algorithmic impact assessments and a right to meaningful human review. In India, the regulatory landscape is in flux — a government advisory requiring pre-deployment approval for “untested” AI models was issued and withdrawn within days.

The general counsel now faces an impossible puzzle: a single AI system, performing a single function, subject to at least five distinct and partially contradictory regulatory regimes, with no international framework to mediate among them.

This is the regulatory reality confronting every company that develops or deploys AI systems across borders. And the number of such companies is growing rapidly. It illustrates the central challenge of international AI governance: the collision between the inherently transnational character of artificial intelligence — the technology does not respect borders in its development, training, or deployment — and the fundamentally territorial logic of state regulation, which organises legal authority along geographic lines.

The burst of regulation

The past five years have produced an extraordinary burst of regulatory activity. The EU’s AI Act — the world’s first comprehensive horizontal AI regulation — entered into force in August 2024. China has issued a succession of targeted algorithmic regulations since 2022. The United States has oscillated between ambitious executive action and deregulatory retrenchment. Brazil, India, Canada, South Korea, Japan, and the African Union have all advanced their own proposals. International bodies from the OECD to the United Nations to the Council of Europe have produced declarations, principles, and even a binding framework convention.

Yet this activity has proceeded largely in parallel, with minimal coordination and often with starkly different underlying philosophies about the relationship between technology, the state, and individual rights. The result is a fragmented global landscape that imposes significant and growing costs: regulatory arbitrage by firms seeking the path of least resistance, interoperability failures that impede cross-border data flows and AI deployment, a deepening digital divide as developing nations find themselves excluded from standard-setting dominated by wealthy states, and mounting geopolitical tension as AI governance becomes entangled with broader contests for technological supremacy.

What history tells us — and where AI breaks the pattern

The tension between technological change and state sovereignty is among the oldest recurring challenges in international law. Each wave of transformative technology — the telegraph, nuclear energy, the internet — has disrupted the territorial assumptions on which the international legal order rests and forced states to develop new governance mechanisms, often haltingly and imperfectly.

The International Telegraph Convention of 1865 is perhaps the most instructive precedent. The telegraph created a communications network whose utility was directly proportional to its geographic reach, and that reach depended on interconnection between networks under different sovereign authorities. The practical imperative of interoperability drove twenty European states to negotiate common technical standards, agreed-upon tariff mechanisms, and routing protocols. The resulting International Telegraph Union succeeded not because states subordinated their sovereignty to a supranational authority, but because the costs of non-cooperation — isolated national networks of limited utility — exceeded the sovereignty costs of coordination. That dynamic — cooperation driven by the functional costs of fragmentation rather than by ideological convergence — is precisely the dynamic that AI governance needs to harness.

The internet governance experience is the most immediately relevant precedent, and it carries a specific warning. Early internet governance was shaped by “cyber-exceptionalism” — the belief that the internet’s decentralised architecture made it inherently resistant to territorial regulation. That ideology proved remarkably powerful as a narrative and remarkably inadequate as a governance strategy. The multi-stakeholder model managed the network’s technical infrastructure effectively but struggled to address broader social, economic, and political consequences. Over the past two decades, states have progressively reasserted sovereign authority over their national portions of the internet — China’s Great Firewall, Russia’s “sovereign internet” law, the EU’s GDPR — fragmenting the once-unified global network along geopolitical lines.

The warning is this: the window for effective international coordination is finite. In the internet’s case, the failure to establish robust multilateral governance mechanisms during the technology’s formative period meant that by the time states began asserting regulatory authority, the governance landscape was already deeply fragmented, and entrenched interests made coordination far more difficult than it would have been earlier. AI governance is arguably at an analogous inflection point right now. If international coordination does not emerge within the next several years, the fragmentation may become self-reinforcing and largely irreversible.

But AI is not simply another iteration of the technology-sovereignty cycle. At least four features distinguish it from its predecessors.

First, opacity. The internal decision-making processes of complex machine learning models are not fully transparent even to their developers. The telegraph, the nuclear reactor, and even the internet are mechanistically comprehensible in ways that current AI systems are not.

Second, generality. AI is applicable to virtually every domain of human endeavour. The same underlying model may be simultaneously subject to health regulation, employment law, financial regulation, and national security law. The regulatory frameworks designed for each of these domains were not built to accommodate a technology that cuts across all of them.

Third, private-sector concentration. AI development is uniquely concentrated in a small number of firms possessing a disproportionate share of computational resources, training data, and technical talent. The entities with the greatest technical knowledge are often the same entities that are the targets of regulation, creating information asymmetries and regulatory capture risks.

Fourth, dual-use character. The same computer vision algorithms that enable autonomous vehicles can guide autonomous weapons. The same natural language processing models that power chatbots can generate sophisticated disinformation at scale. This means AI governance inevitably implicates national security considerations, which makes international cooperation far harder.

These four features interact and compound one another, and together they explain why the governance task is so difficult and why the international community has thus far failed to rise to it.

What the major jurisdictions are actually doing

Beneath the surface divergences of the world’s AI regulatory regimes lies a story that is more complex — and more hopeful — than the standard narrative of irreconcilable conflict suggests.

The EU has built the world’s most elaborate regulatory architecture. The AI Act rests on a risk-based classification system assigning AI systems to four tiers, from prohibited practices at the top to minimal-risk systems at the bottom. High-risk systems face mandatory risk management, conformity assessments, technical documentation, transparency, and human oversight requirements. The Act’s territorial scope is deliberately extraterritorial: any company in the world seeking access to the EU’s 450 million consumers must comply. This is the Brussels Effect in action — the same dynamic that made the GDPR a de facto global data protection standard. The Act also includes novel provisions addressing general-purpose AI models, regulating the underlying technology rather than just its applications.

China has taken a sectoral and iterative approach — a series of targeted regulations addressing specific AI applications as they emerge. The Algorithm Recommendation Provisions (2022), Deep Synthesis Provisions (2023), and Generative AI Measures (2023) each target a specific technological category rather than establishing a unified framework. This allows regulators to respond quickly — the Generative AI Measures were issued within approximately eight months of ChatGPT’s release, while the EU AI Act required over three years. Each regulation includes transparency requirements, anti-discrimination provisions, and user opt-out rights that overlap functionally with Western frameworks. Each also includes provisions with no Western parallel: requirements to “uphold mainstream value orientations,” “actively disseminate positive energy,” and ensure content “adheres to socialist core values.” These provisions transform AI regulation from a tool for managing technical risk into an instrument of political control. But focusing exclusively on the ideological elements — as Western commentary often does — obscures the significant overlap on technical and procedural dimensions.

The United States occupies a paradoxical position: home to the world’s most advanced AI companies yet lacking any comprehensive federal AI legislation. The Biden Executive Order of October 2023 established sweeping AI safety measures and invoked the Defense Production Act to require safety test reporting for the most powerful models. It was revoked in its entirety by the Trump administration on January 20, 2025. That reversal illustrates a structural vulnerability of the executive-order approach: policies established by one president through executive authority can be dismantled by the next, creating a regulatory instability that undermines predictability for both firms and international partners. In the federal vacuum, existing sectoral regulators — the FTC, FDA, EEOC — have begun exercising their existing authorities, and state legislatures have moved aggressively, with over seven hundred AI-related bills introduced in state legislatures during 2024 alone. The result is the international fragmentation problem reproduced domestically.

Brazil’s AI Bill, approved by the Senate in December 2024, represents one of the most ambitious proposals outside the EU-US-China triad. It adopts a risk-based system but departs from the EU model by placing stronger emphasis on fundamental rights, establishing a dedicated regulatory authority, and guaranteeing an individually enforceable right to meaningful human review of automated decisions. India’s approach has been markedly less stable — a sweeping advisory requiring government pre-approval for “untested” AI models was issued and withdrawn within days after industry backlash. The African Union’s Continental AI Strategy takes a fundamentally different approach, focusing not on prescriptive rules but on building the institutional, human capital, and data infrastructure necessary for African states to participate meaningfully in the AI economy at all.

Where they converge — and where they don’t

A functionalist comparison — looking not at formal doctrinal categories but at the regulatory problems each system is trying to solve — reveals more convergence than the headlines suggest.

Nearly every major jurisdiction has embraced some form of risk proportionality: not all AI systems require the same regulatory attention, and obligations should be calibrated to the severity of risks. Transparency requirements appear in every regime, though they vary in mechanism — the EU mandates technical documentation, China channels disclosure toward the state, the US relies on voluntary model cards. Every jurisdiction recognises that consequential AI-driven decisions require some mechanism for human oversight or intervention. And every regime includes some form of pre-deployment or ongoing assessment — conformity assessments, security assessments, impact assessments, safety testing. There is also a growing recognition that general-purpose AI models require distinct regulatory treatment, though this convergence remains tentative.

Against these convergences, three major divergences complicate any project of international coordination. The first is foundational: the EU’s rights-based approach, China’s integration of AI regulation with political control, the US’s market-oriented default, and the Global South’s emphasis on equitable participation represent fundamentally different visions of the purpose of AI governance. These differences reflect deep disagreements about the relationship between technology, the state, and the individual that are unlikely to be resolved through negotiation. The second concerns the weight given to innovation versus precaution — the EU’s willingness to impose binding ex ante obligations versus the US’s preference for ex post enforcement and voluntary standards. The third concerns national security and geopolitical competition — US export controls on advanced semiconductors, the expansion of the Entity List, and China’s retaliatory measures have transformed AI governance from a primarily domestic regulatory question into a geopolitical battleground.

The costs of doing nothing

The fragmentation is not merely inconvenient. It is actively harmful along four dimensions.

Regulatory arbitrage. When obligations vary significantly across jurisdictions, firms face rational incentives to concentrate their most regulation-sensitive activities in the least demanding environments. Several major AI developers have already delayed or limited rollout of services in the EU, citing compliance uncertainty. The Trump administration’s explicit framing of AI governance as a barrier to American competitiveness signals a strategic choice to position the US as a lower-regulation alternative — intensifying pressure on other jurisdictions to follow suit. The costs fall not on the firms that engage in arbitrage but on the individuals whose rights are at stake when AI systems operate in governance gaps.

Interoperability failures. No mutual recognition mechanism exists for AI governance. A conformity assessment conducted under the EU AI Act is not recognised anywhere else. China’s algorithm-filing system is not recognised outside China. Each jurisdiction’s regulatory process operates as a self-contained silo, requiring firms to repeat functionally similar compliance procedures in every market they wish to serve. This functions, in practice, as a barrier to digital trade.

Deepening digital divides. Most states in the Global South lack the regulatory expertise, technical capacity, and financial resources to develop and enforce comprehensive AI regulation. They also lack the market power to exercise a Brussels Effect. The result is a two-tier global governance landscape in which wealthy states write the rules and developing states are relegated to the role of passive consumers of AI systems designed, trained, and regulated elsewhere. AI systems trained primarily on data from wealthy countries may perform poorly in developing-country contexts — healthcare diagnostics less accurate for different demographic profiles, agricultural tools optimised for conditions that don’t apply.

National security externalities. The securitisation of AI governance — its progressive entanglement with geopolitical competition — makes states reluctant to accept governance constraints on technologies they view as essential to military advantage, reduces trust between potential governance partners, and creates a dynamic in which AI governance becomes a tool of rivalry rather than a mechanism for managing shared risk.

Layered pluralism: a framework that might actually work

A single comprehensive international AI treaty is neither politically feasible nor, given the speed of technological change, desirable. The political conditions do not exist. The pace of multilateral treaty negotiation is fundamentally incompatible with AI’s rate of evolution. And premature consensus would foreclose valuable regulatory experimentation.

What the situation demands instead is what might be called layered pluralism — a governance architecture that imposes structure on diversity without requiring uniformity. It operates on three levels.

Layer One: A floor of minimum standards. A small number of non-derogable standards addressing risks on which broad consensus either exists or is achievable. Three candidates: a prohibition on autonomous weapons systems designed to select and engage human targets without meaningful human control; a prohibition on AI-enabled mass surveillance without judicial oversight; and mandatory disclosure requirements for AI-generated content used in democratic processes. These are deliberately narrow — addressing only those applications whose risks are both catastrophic and widely acknowledged.

Layer Two: Mutual recognition corridors. Bilateral or plurilateral agreements through which jurisdictions with functionally equivalent regulatory approaches recognise each other’s conformity assessments, eliminating duplicative compliance procedures. The model here is the Basel Accords in international financial regulation. The Basel Committee develops common standards through negotiation, peer review, and mutual assessment. The standards are not legally binding — they are implemented through domestic regulation in each jurisdiction. Compliance is monitored through peer review. The system achieves convergence not through legal obligation but through reputational incentives, peer pressure, and the practical benefits of coordination. A similar structure could be adapted for AI governance, with jurisdictions assessing each other’s frameworks across the convergent dimensions — risk proportionality, transparency, human oversight, pre-deployment assessment — and entering into recognition agreements where functional equivalence is established.

Layer Three: An institutional canopy. Rather than creating a new international organisation, the proposal strengthens and connects existing institutions through a coordinated network. The OECD would serve as the primary node for standard development, peer review, and mutual recognition administration. The United Nations would ensure inclusive governance and translate minimum standards into actionable commitments. Regional bodies — the African Union, ASEAN, the Organisation of American States — would adapt global principles to regional circumstances and channel technical assistance. Critically, this layer must include robust capacity-building mechanisms: technology transfer, regulatory training, equitable data governance arrangements, and provisions for sharing AI’s economic benefits. Without these, the architecture risks replicating existing asymmetries under a more sophisticated institutional veneer.

Answering the obvious objections

“This is just another word for inaction.” No. There is a fundamental difference between unstructured fragmentation — jurisdictions proliferating frameworks without coordination — and principled pluralism with minimum standards, mutual recognition, and institutional coordination. The former is what we have now. The latter is a governance architecture that respects diversity while mitigating its costs.

“Authoritarian states will never agree to meaningful standards.” The historical record says otherwise. The Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, the Non-Proliferation Treaty, and the Outer Space Treaty were all negotiated between the United States and the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. These agreements did not require ideological convergence — they required a shared perception that uncoordinated action posed unacceptable risks to both parties. Moreover, layered pluralism is explicitly designed to function even without comprehensive agreement from authoritarian states. The minimum standards address risks on which broad consensus is achievable. The mutual recognition corridors are voluntary. The institutional canopy is inclusive but not dependent on unanimity.

“The technology moves too fast for any framework.” This objection confuses the speed of technological change with the impossibility of governance. What the speed of change actually requires is governance designed for adaptability rather than permanence. Minimum standards articulated as principles rather than prescriptive rules. Mutual recognition agreements with provisions for periodic reassessment. Institutional horizon-scanning to identify emerging challenges before they become crises. The Basel Accords have been revised three times since 1988, adapting to developments in financial markets and incorporating lessons from successive crises. An AI governance architecture modelled on this adaptive design can similarly evolve.

The closing window

Return to the multinational company’s general counsel. Under a layered pluralism framework, she would face a fundamentally different landscape. Minimum standards would establish clear, universally applicable red lines — certain uses of AI in hiring would be prohibited everywhere. Mutual recognition corridors would allow a single conformity assessment recognised across participating jurisdictions. And the institutional canopy would provide a forum for resolving residual conflicts and updating the framework as the technology evolves.

The window for effective coordination is narrowing. The regulatory approaches of the major jurisdictions are hardening. The costs of fragmentation are compounding. And the technology continues to advance at a pace that leaves less and less room for leisurely deliberation. The question is not whether the international community will eventually need to coordinate on AI governance. It is whether it will do so proactively — through a structured framework that manages diversity while maintaining minimum standards — or reactively, in the aftermath of a crisis that forces cooperation under conditions of urgency and unequal power.

The choice, for now, remains open. But not for much longer.

When posed that way by Dr Wright - that we are in a fork in the road moment - it seems obvious that the later is the most likely outcome given the geopolitics and economics around China and capex cycle.

Again, it seems so obvious now and simple after the read.

Believe in the power of prayer? We are going to need it.

And Happy St Valentine’s Day, everyone! It will be okay.