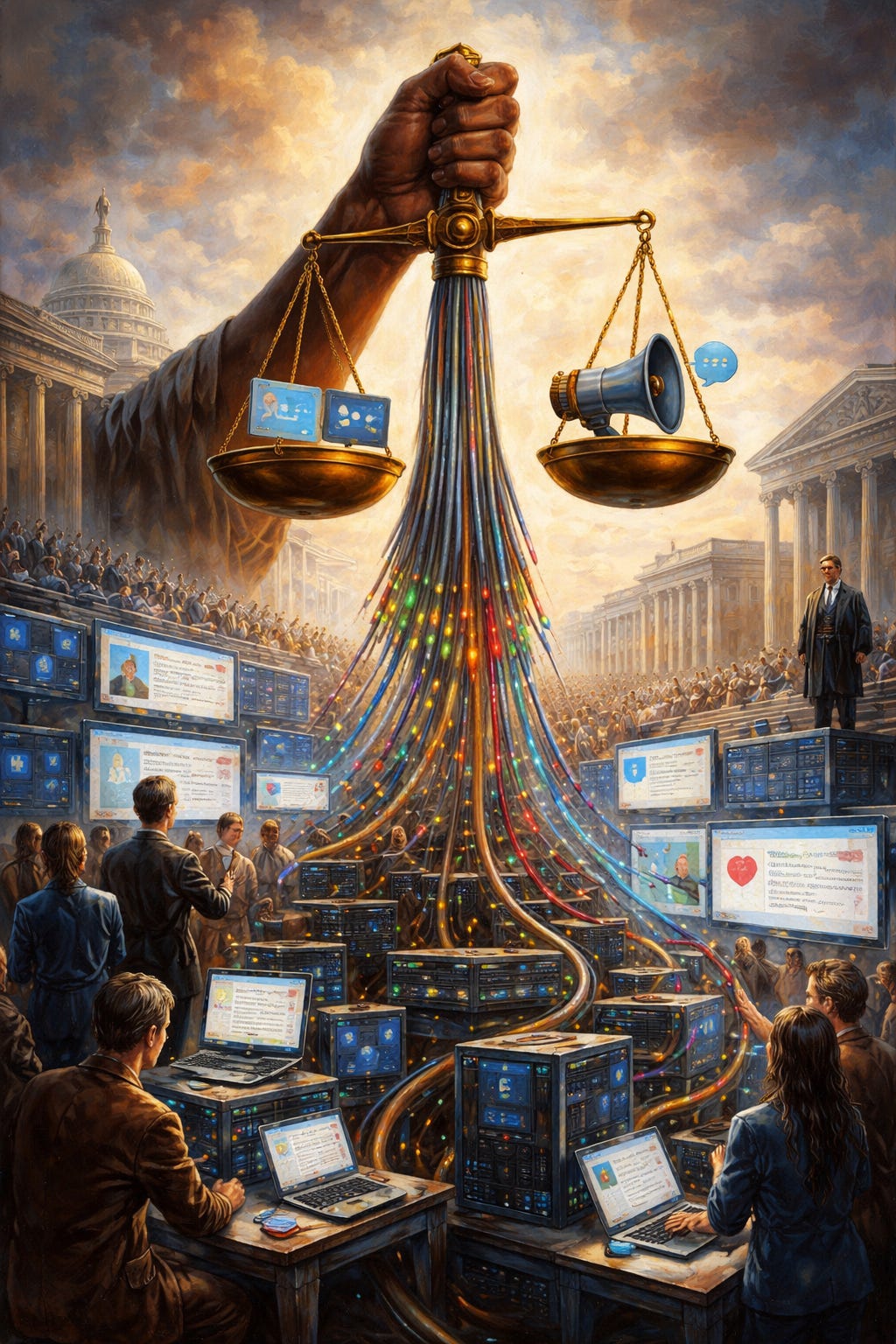

Speech as Infrastructure

Why Content Moderation Is a Public Utility Problem

1. The category mistake the Court keeps inheriting

The American constitutional debate over platform moderation is routinely staged as a duel between speakers. The state claims to protect the speech of users who are removed, downranked, or otherwise impeded. The platforms claim to protect their own speech in choosing what to carry, what to elevate, and what to suppress. The result is a familiar, almost ritualised frame: speech-versus-speech, as if the entire system were an editorial page where every act of ordering is an authored opinion.

That frame fails at the point where moderation is no longer a small number of human editorial decisions and instead becomes large-scale, automated allocation of reach. Once the dominant decisions are made through ranking, recommendation, suppression, friction, demonetisation, and account limits applied as defaults across millions of items, the relevant question stops being “what does the platform intend to say?” and becomes “what routing power does the platform retain, and how does that control allocate access to attention?”

The Supreme Court’s consolidated decisions in Moody v NetChoice, LLC and NetChoice, LLC v Paxton did not resolve the merits of the Florida and Texas statutes. They vacated and remanded because the lower courts did not perform the proper analysis for facial First Amendment challenges and did not examine the full range of the laws’ applications across the platforms’ many functions. (supremecourt.gov) That procedural posture matters. It is a doctrinal instruction that forces courts—if they follow it honestly—to stop arguing by analogy to newspapers and start mapping the actual system: functions, surfaces of control, and the breadth of the regulatory target.

That mapping exercise exposes the foundational misclassification. At scale, moderation is not best understood as expression. It is infrastructure.

2. What “moderation” actually does at scale

If one takes the word “moderation” seriously as a description of system behaviour, it describes allocation. It determines who is heard, by whom, at what frequency, and under what friction. It does this through routing and amplification. The core mechanisms are not mysterious. They are the ordinary tools of optimisation systems: ranking functions, recommendation graphs, admission controls, queueing policies, thresholds that trigger suppression or removal, rate limits that constrain propagation, and default settings that determine what happens absent an individualised human decision.

These are not merely implementation details. They are the thing. They decide whether speech reaches an audience at all, and if so, whether it arrives as a whisper buried beneath noise or as a shout placed at the top of a feed. They decide whether discovery is possible through search, whether sharing triggers friction, whether a post is eligible for monetisation, whether the account is eligible for recommendation, whether the content can be embedded or linked, whether it can appear in “trending” or similar high-exposure modules. These are the levers of attention.

An editorial model treats these outputs as speech because it imagines a human editor selecting content to make a statement. But the system’s dominant behaviour is not a statement. It is a routing regime. What matters for routing regimes is not intent; it is retained discretion over defaults.

That is why the compelled-speech argument, as it is commonly presented, becomes unstable. One cannot coherently claim that a requirement to carry without viewpoint discrimination “forces speech” when the relevant act is not endorsement but nondiscriminatory access to a conduit whose defining feature is that it carries others’ speech. The law has long managed this distinction in other contexts. It has not done so cleanly in the platform context because it has allowed itself to believe the “editor” metaphor.

3. The NetChoice remand instruction as an opportunity rather than a setback

In Moody/Paxton, the Court’s key move was to insist on proper facial-challenge analysis and on attention to the full range of regulated functions. (supremecourt.gov) That requirement is often read as delay, but it also contains a methodological demand that is lethal to superficial analogies.

Platforms are not single-purpose entities. They have many functions. They host user speech. They produce and commission their own content. They label and annotate. They sell advertising. They operate recommendation engines. They provide messaging and group functions. They maintain search and discovery. They provide APIs and embed systems. They offer creator tools. They have complaint-and-appeal mechanisms. They have safety systems that are partly behavioural and partly content-based.

A court forced to take this multiplicity seriously cannot plausibly treat every function as editorial speech. Some functions are plainly expressive products. Others are plainly infrastructural services. The insistence on scope, if honoured, pushes the doctrine towards functional decomposition: what is being regulated, which function is at issue, and what kind of power is being constrained?

That is precisely the terrain where “speech as infrastructure” becomes the clean solution. It does not require the court to deny that platforms ever speak. It requires the court to stop pretending that routing defaults are the same category as authored messages.

4. Public utility and common carriage as the correct constitutional analogue

The public utility and common carriage traditions exist because certain systems, by their structure, become bottlenecks for interaction. When the primary value of the service is that it conveys other people’s communications, the law has historically been willing to impose access and nondiscrimination obligations without treating those obligations as compelled endorsement.

Texas HB 20 makes the analogy explicit by describing large platforms as common carriers and by regulating “censorship” practices defined broadly to include de-boosting, demonetisation, and visibility denial. (capitol.texas.gov) Florida’s SB 7072 takes a different approach, including restrictions on deplatforming candidates and special protections for certain journalistic enterprises, backed by significant fines in some contexts. (flsenate.gov)

One need not defend every drafting choice in either statute to recognise what the statutes are grasping at: the feeling that something has become infrastructural, and that the old editorial model is not describing the relevant power. The question is whether constitutional doctrine can articulate the correct principle with better discipline and cleaner limiting rules than these legislative experiments.

The infrastructural analogue does that work. It takes seriously the idea that the central harm is not the platform’s expression. It is discriminatory allocation in a system controlling the routing of others’ speech at scale, where exit is costly and attention is the scarce resource being allocated.

Under this view, the constitutional predicate is not “is the platform like a newspaper?” It is “is the platform operating a routing infrastructure whose defaults allocate access to attention, and is the state imposing viewpoint-neutral duties on that allocation function?” If yes, the compelled-speech objection weakens, because the regulated conduct is better understood as infrastructural service rather than authored expression.

5. Severing First Amendment analysis from intent

The most important methodological break is to stop using intent as the anchor. Intent is conceptually attractive because it feels like the heart of speech. But when moderation is implemented through automated defaults, intent does not explain outcomes. Parameter choices do. Thresholds do. Deployment pathways do. Feedback loops do.

A system can produce a pattern of amplification and suppression without any human forming an intention about any particular item. It can also produce that pattern while employees sincerely deny that they intended it. The system’s practical effects are nonetheless real, systematic, and stable enough to create reliance and to shape public discourse.

Once one recognises this, the legal question becomes: who controls the routing defaults, and what constraints exist on that control? That is a control-based predicate, not an intent-based predicate. It is closer to the way utility regulation conceptualises power: control over access, not endorsement of content.

This is not a trick to evade the First Amendment. It is the only approach that matches the object under analysis. If doctrine insists on forcing automated allocation into an intent-centred frame, it will oscillate between two errors. It will either treat the entire infrastructure as pure speech, immunising routing power from meaningful constraint; or it will treat the entire enterprise as mere conduct, enabling blunt regulation. The infrastructure approach avoids both by splitting functions and matching scrutiny to function.

6. Routing defaults as the legal object

“Routing defaults” should be treated as a justiciable object. It is definable in operational terms a court can understand and evidence can prove.

A routing default is the baseline path an item takes through a system absent an individualised, item-specific editorial act. It is the path determined by standing rules: ranking weights, eligibility gates, suppression triggers, sharing limits, and discovery affordances. It includes the default amplification channels (feeds, recommendations, “next up” panels), default suppression channels (downranking, de-indexing, reduced distribution), and default frictions (warnings, click-through barriers, rate-limited sharing).

The decisive point is that routing defaults are applied at scale. They are, by design, repeatable and general. They produce system-level allocation. That is why they have a public-utility character. They are not one-off “choices” in the ordinary speech sense; they are constitutive constraints on who gets heard.

Once that is the object, the evidentiary posture changes. The relevant evidence is not primarily “what did the platform mean?” It is “what are the routing rules, who can change them, under what process, and with what constraints?” That is the kind of question courts already know how to address when they regulate power over access.

7. Transaction-cost economics and the failure of the “just leave” premise

The editorial model often smuggles in an exit story. If a user dislikes the platform’s moderation, the user can leave. If a speaker is suppressed, the speaker can take their message elsewhere. If audiences dislike the platform’s choices, they can move.

At scale, this is a fiction. It is not a moral accusation; it is a description of costs. In large networks, exit is expensive because value is locked into social graphs, reputational capital, audience accumulation, and cross-platform embedding. The platform’s defaults are not merely preferences; they are the conditions of reach within a high-switching-cost environment.

That is why the analogy to utilities is not ornamental. Utilities are regulated precisely because exit is not a meaningful remedy for many users, and because discriminatory access rules create system-level harms. A legal system that treats high-switching-cost infrastructures as though they were fully contestable markets will misdiagnose harm and misallocate remedies.

The “speech as infrastructure” frame therefore imports a familiar economic insight: when transaction costs are high and the service is a bottleneck, private allocation decisions can have public consequences that are not well addressed by telling individuals to bear the costs of exit.

8. Network theory: moderation as flow control rather than expression

The infrastructural view becomes clearer when one models the system as a network of flows. Attention and reach function like flows through constrained channels. The platform controls edge weights (how likely content is to be forwarded to the next node), gate nodes (eligibility for recommendation), and congestion policies (what is prioritised under scarcity). Changing a weight can have effects analogous to opening or narrowing a valve.

This is not metaphor. It is an accurate description of how optimisation systems allocate exposure. The platform’s power is the power to control the network’s effective topology for speech: which routes exist, which are widened, which are narrowed, and which are closed.

If that is the structure of the power, the legal analogue to editorial discretion is weak. Editorial discretion is about authored selection to communicate a message. Flow control is about allocating capacity under scarcity. One can allocate capacity neutrally or discriminatorily. One can justify capacity rules by safety, fraud prevention, and system integrity. One can also hide viewpoint discrimination inside technical proxies. But the category is not “speech”; it is infrastructural allocation with expressive consequences.

9. Dissolving the compelled-speech objection while preserving real expressive autonomy

The infrastructure frame does not require hostility to platform speech. It requires precision about what counts as platform speech.

Platforms do speak when they produce their own content, when they issue statements, when they label content with platform-authored text, when they create curated editorial products presented as the platform’s own message, and when they commission and publish expressive works under the platform’s brand. Those functions deserve the strongest First Amendment protection.

But the routing infrastructure is different. It is the mechanism by which others’ speech is conveyed and distributed. A nondiscrimination obligation applied to that function is not inherently compelled endorsement. It is a constraint on discriminatory allocation by a bottleneck.

This dissolves the standard compelled-speech objection in its broad form. It does not guarantee that any particular statute will survive. It changes the argument’s centre of gravity. Instead of treating the platform as a single speaker with a single editorial will, it forces the court to ask which function is being regulated and whether the obligation is imposed on an infrastructure function or an expressive product.

The result is a doctrinal settlement that is both more protective and more realistic: it protects platforms where they genuinely speak and permits carefully limited constraints where platforms operate a speech-routing utility.

10. A court-usable doctrinal sequence after Moody/Paxton

The remand posture in Moody/Paxton supplies the procedural scaffolding. (congress.gov) The doctrinal sequence that follows from the infrastructure view can be stated cleanly.

First, the court decomposes the platform into functions implicated by the statute: hosting, ranking, recommending, searching, messaging, labelling, commissioning, advertising, and so on.

Second, the court classifies each regulated function as either an expressive product (platform-authored or platform-presented editorial expression) or an infrastructure function (routing, access, and default distribution of others’ speech).

Third, the court evaluates the statute as applied to each function rather than as an undifferentiated whole, because the First Amendment interests are not uniform across functions.

Fourth, the court evaluates compelled-speech claims with that classification in view. Where the statute constrains infrastructure functions through viewpoint-neutral access rules, the claim that the platform is being forced to “speak” is, at minimum, substantially weaker than when the statute compels platform-authored messaging or platform-curated editorial content.

Fifth, remedies follow the same decomposition. Narrow relief can target infrastructure constraints without rewriting the platform’s expressive products, and vice versa.

This is not an invitation to judicial engineering. It is an insistence on ordinary judicial classification: identify the thing, match the doctrine to the thing, and tailor relief to the thing.

11. Limiting principles: when infrastructure is actually neutral

Any serious argument for an infrastructure analogue must contain limiting principles that prevent the concept from swallowing legitimate private discretion. The infrastructure frame supplies them naturally.

The first limit is retained discretion. Where the platform truly does not retain discretionary control—where rules are fixed, transparent, and verifiable—claims of discriminatory allocation become harder, and the justification for utility-like constraints weakens.

The second limit is function-specific scope. Infrastructure duties attach to routing defaults, not to the platform’s own speech. They do not force a platform to author messages, endorse viewpoints, or publish original editorial content.

The third limit is viewpoint neutrality in regulation. A state that uses the “utility” label to impose viewpoint-driven allocation rules is not regulating infrastructure; it is capturing the routing system for political ends. The infrastructure view, properly applied, makes that abuse easier to identify, because it demands rule-like constraints rather than discretionary state control.

The fourth limit is genuine exit and substitutability. Where users can realistically move with low cost, and where interoperability or portability reduces lock-in, the case for public-utility style constraints is weaker. Infrastructure is not a moral category; it is a structural one.

These limits do not answer every case. They make the doctrine usable, and they prevent the analysis from devolving into metaphors.

12. What evidence becomes central once the object is routing defaults

Once routing defaults are the predicate, courts and litigants must stop litigating solely about abstract analogies and start litigating about operational control.

The critical evidence includes change-control logs for ranking and suppression parameters; governance structures for policy changes; deployment pipelines showing how updates are shipped; documentation for classifier thresholds and error trade-offs; A/B testing records that reveal intentional amplification or suppression effects; escalation channels and override authority; complaint and appeal workflows; and internal definitions of “visibility” categories (eligible, ineligible, limited, excluded).

This is also where Moody/Paxton matters again. The Court’s insistence on full-scope analysis is a practical demand for full-scope record development. (supremecourt.gov) Courts cannot meaningfully assess a facial challenge about “platform moderation” if they treat moderation as a single act rather than a multi-surface system. The infrastructure frame tells them what to ask for.

13. The doctrinal payoff: rebuilding First Amendment reasoning for digital intermediaries

The deepest claim here is not political. It is jurisprudential. A constitutional system cannot coherently allocate rights and duties if it cannot classify the relevant activity.

Treating routing infrastructure as pure speech collapses the distinction between authored expression and allocation power. It invites an overbroad immunity for bottleneck control, because any constraint can be recast as “compelled speech.” Treating the system as mere conduct invites the opposite error: blunt control over speech distribution by the state. The infrastructure frame avoids both errors by being literal about what the system does.

It says: the central modern power is control over routing defaults. That power allocates reach. That allocation is infrastructural. The First Amendment remains central, but it attaches differently: strongly to the platform’s own expression, and differently—more like carriage—to the infrastructure function by which the platform allocates the distribution of others’ speech.

The result is not a downgrade of free expression. It is the restoration of doctrinal realism. It forces courts to confront the real mechanism of influence in the digital public sphere: not a single editorial “voice,” but a set of control surfaces governing routing, amplification, and suppression at scale.

14. Conclusion: the correct object restores doctrinal coherence

The NetChoice litigation has been treated as a referendum on whether platforms are newspapers. The better reading is that it is forcing courts to admit that platforms are systems, and that the relevant constitutional object is not intention but control over routing defaults. (SCOTUSblog)

When moderation is automated and scaled, it functions as infrastructural allocation. The constitutional analogue is therefore common carriage and public utility law applied to routing and access, not an editorial discretion model applied indiscriminately to every platform function.

Once that reclassification is made, the compelled-speech objection loses its sweeping force without sacrificing genuine expressive autonomy. The law stops pretending that valves are op-eds, and it becomes capable—again—of describing power with accuracy before attempting to constrain it.