The Discipline of Rest: A Sunday Reflection on Work, Truth, and Renewal

Why Rest Is Not Idleness, and Reflection Is the Highest Form of Work

Keywords:

Rest; Work; Truth; Discipline; Reflection; Integrity; Wesleyan Ethics; Individual Responsibility; Purpose; Creation; Renewal; Moral Agency; Productive Stillness

I. Introduction – The Misunderstanding of Rest

We live in an age that worships work yet knows nothing of rest. The modern world is built upon a feverish rhythm—an unending cycle of production, consumption, and self-display. It is a civilisation that measures worth in motion, that confuses exhaustion with achievement and silence with failure. Yet beneath the din of activity lies a profound unease: for all its efficiency, the modern individual is incapable of peace. He knows how to labour endlessly but not how to stop; how to accumulate, but not how to reflect. His rest, when it comes, is not peace but paralysis—a collapse of will mistaken for restoration.

Rest, once understood as renewal, has been degraded into escape. It is sold as distraction, packaged as indulgence, and consumed as anaesthesia. To rest now means to disconnect from responsibility, to flee the self in a haze of entertainment, or to seek comfort in the shallow immediacy of pleasure. This counterfeit rest offers relief but never restoration. It dulls the senses instead of sharpening them; it numbs the mind instead of ordering it. The individual emerges from such idleness not strengthened, but diminished—more restless, more dependent, more uncertain of purpose.

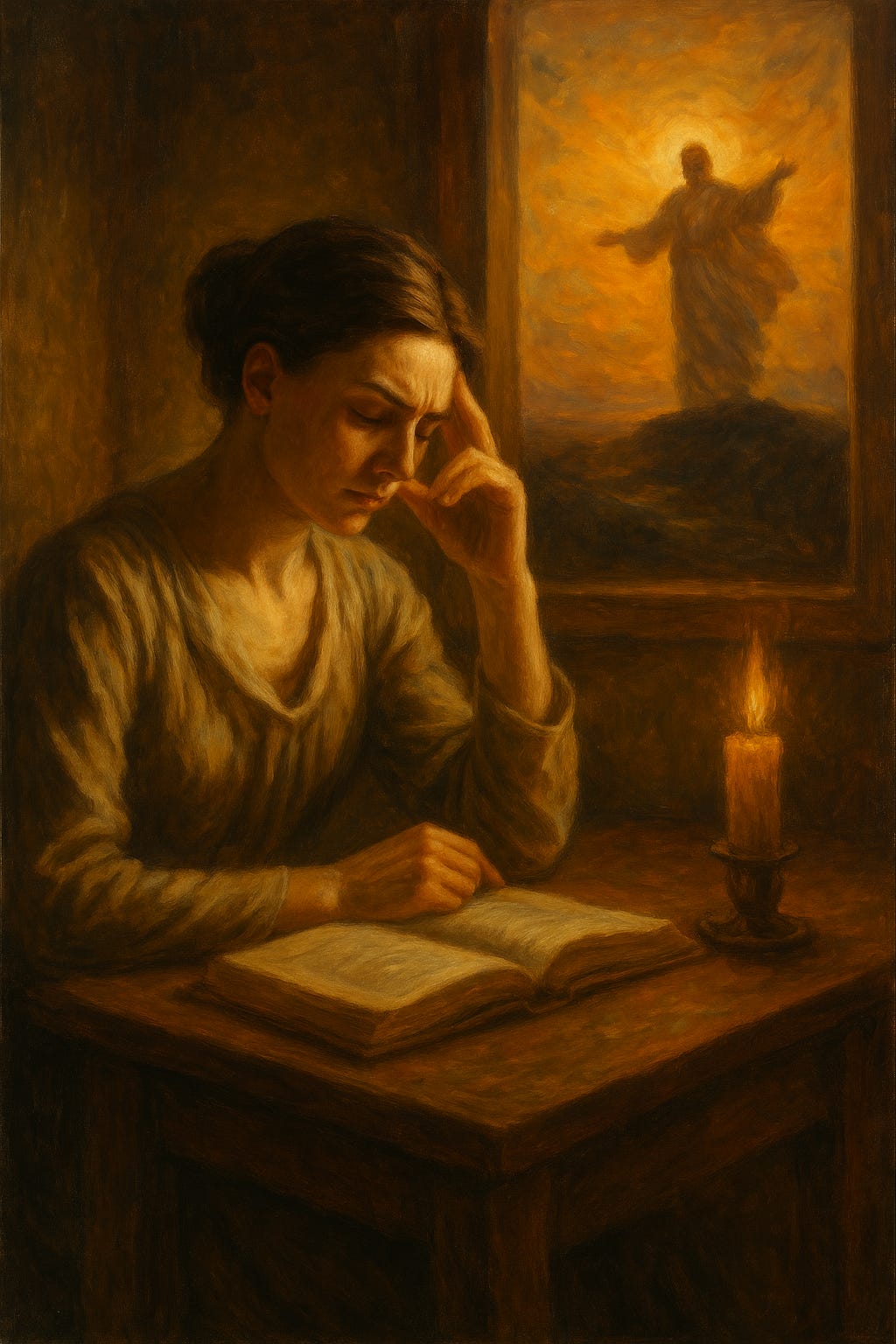

True rest is something entirely different. It is not the negation of work but its continuation by higher means. It is the conscious discipline of stepping back, not to surrender, but to see more clearly. It is the deliberate re-gathering of one’s strength, an inward act of reflection through which the mind realigns itself with truth. Rest, rightly understood, is not a withdrawal from effort but a moral discipline—a rehearsal of integrity. It demands as much will as labour itself, for it requires mastery over the urge to drift into apathy.

Here the philosophies of Ayn Rand and John Wesley converge: both insist that the moral life is not passive but purposeful. Rand’s celebration of reason and productive achievement meets Wesley’s vision of holiness through disciplined living. Rest, therefore, is not leisure but self-command—a moment of spiritual and intellectual recalibration where the individual reclaims dominion over thought, time, and will.

True rest is an act of moral self-governance. It is the conscious reordering of one’s being toward truth, integrity, and purposeful work. To rest rightly is not to escape from life’s demands, but to prepare to meet them with greater clarity, courage, and conviction. In rest, we do not abandon creation—we prepare to begin it anew.

II. The Ethics of Work

Work is not a punishment, nor is it a mere necessity—it is the most visible expression of the will. In the act of creation, a person declares who they are and what they believe. Every task, however small, is a moral statement: it reflects discipline, conviction, and one’s relationship with truth. The dignity of labour lies in this alignment between action and principle. To work rightly is not to toil blindly but to transform effort into meaning. It is, in essence, the art of making the invisible visible—translating inner conviction into tangible form.

Ayn Rand saw productive achievement as the highest moral purpose of life. To create, in her view, is to affirm existence—to say, “I am, and I will make.” Work, stripped of servility and redefined as creative effort, becomes the embodiment of reason and self-respect. In labour done freely and with vision, man transforms the world and himself. John Wesley, writing from a different tradition, saw work as sanctified service—a means by which the individual participates in divine order. His ethic was not of pride but of stewardship: to work diligently, honestly, and without waste, as a sign of grace made manifest through effort.

Though their languages diverge—Rand’s humanistic rationalism and Wesley’s Christian devotion—their conclusions converge. Both reject idleness as moral decay. Both see in work a sacred duty: the pursuit of excellence, the exercise of integrity, the manifestation of truth. Where Rand speaks of creative power, Wesley speaks of moral calling—but the substance is the same. Work, rightly conceived, is not exploitation but expression. It is not slavery but freedom—the disciplined use of one’s strength in harmony with purpose.

When work loses that connection to truth, it becomes a form of quiet despair. Fatigue, cynicism, and spiritual exhaustion arise not from labour itself, but from labour emptied of conviction. The modern worker, alienated from meaning, performs tasks without ownership, effort without vision. He works for approval, for gain, or simply out of inertia—his hands moving while his mind retreats. This detachment breeds the cynicism of the soul: the sense that work consumes but does not create, that time is spent but never lived.

Rest, therefore, is not the enemy of work but its moral counterpart. It is the antidote to disconnection, the space in which labour is re-aligned with integrity. In rest, one does not abandon effort; one reclaims the reason for it. It is a moment of inward repair, where fatigue becomes reflection and habit becomes choice again. Just as work without truth destroys the spirit, rest without purpose dulls it—but together they form the rhythm of a life rightly ordered: creation followed by contemplation, action renewed through understanding. To work well, one must also learn to rest well—for rest is where the worker becomes whole.

III. The Sabbath of the Mind

The Sabbath has long been misunderstood. It is often imagined as a retreat from labour, a time of idleness, a divine holiday from the burdens of the week. Yet in its truest sense, the Sabbath was never meant for laziness but for liberation—for the mind to step beyond the noise of motion and examine the purpose of its path. To rest, in this sacred sense, is not to cease living but to live more consciously. It is to suspend the ceaseless activity of doing, so that one may return to the deeper act of being.

A mind that never stops producing inevitably ceases to think. The rhythm of constant motion breeds not creation but repetition. In the modern world, we have mistaken activity for awareness, output for insight. We confuse the clatter of productivity with the clarity of thought. The result is a generation of individuals who are perpetually in motion but perpetually lost—exhausted by the velocity of their own doing, unable to recall why they began to move in the first place. A machine can produce endlessly, but only a mind that pauses can discern whether it is producing anything of value.

The Sabbath of the mind is therefore not a pause from life but a deliberate act of consciousness. It is the discipline of reflection—the choice to stand outside one’s momentum and evaluate its direction. It is a reckoning, not a retreat. The soul, left unexamined, becomes mechanical; it operates efficiently yet meaninglessly. Reflection breaks that automatism. It restores freedom by reuniting thought with will. To rest in this way is to awaken the intellect from its trance of utility, to ask: Am I still creating, or merely continuing?

In Wesleyan theology, such reflection is an act of accountability. The Sabbath is a dialogue between the soul and its Maker, a time when one confronts one’s own motives and measures them against the eternal. To rest is to submit the self to judgement—not of law, but of conscience. It is not passive, for it demands courage: the courage to see oneself clearly. From Wesley’s perspective, the Sabbath is not rest from labour but the sanctification of it, a moral audit in which work and will are reconciled with grace.

From the perspective of Rand’s rational egoism, reflection serves a parallel function: it is the self-audit of reason. The individual, as moral agent, must continually examine whether his actions arise from conviction or conformity. For both thinkers, truth is the ultimate measure, and reflection is the means by which one aligns action with truth. Rest, then, becomes a process of intellectual honesty—the reassertion of integrity against the chaos of distraction.

To rest rightly is to engage in the most demanding of labours: to confront oneself. It is to measure one’s actions not by convenience or approval but by principle. The Sabbath of the mind is not a quiet indulgence; it is a solemn renewal of purpose. In that stillness, work is not abandoned but clarified, and the individual stands once more in the light of deliberate truth.

IV. The Discipline of Stillness

Stillness is not ease—it is effort. The ability to stop, to silence the world within and without, demands more discipline than the feverish labour of constant motion. To be still without becoming stagnant is one of the highest forms of strength, for it requires mastery over the restless mind and mastery, too, over the ego that confuses activity with virtue. True stillness is not the absence of work; it is the presence of control.

The modern cult of busyness has transformed activity into a moral ideal. People boast of exhaustion as if fatigue were a badge of honour. Every moment must be filled, every silence conquered. The idle are condemned not for sloth, but for threatening the collective illusion that motion equals meaning. Yet beneath the façade of diligence lies fear—fear of reflection, fear of seeing one’s own emptiness when the noise stops. Busyness has become the last refuge of those who dread thought. The worker who never pauses to think is praised as “dedicated,” though he is merely obedient to chaos.

Stillness, by contrast, is an act of restraint. It demands the will to cease movement without collapsing into apathy, the courage to resist both exhaustion and indulgence. It is not idleness but equilibrium. To be still is to gather the scattered energies of the mind, to restore unity where distraction has divided. It is a form of moral fasting—the deliberate withholding of impulse so that the soul may regain its appetite for meaning.

Nature teaches this truth with quiet eloquence. A field must lie fallow to yield again; a forest regrows only through seasons of stillness. Rivers deepen when their currents slow. Likewise, the human mind must rest—not as retreat, but as renewal. Without pause, creativity burns out; without silence, wisdom cannot speak. The greatest thinkers, artists, and reformers have understood this rhythm: work and stillness as two halves of the same creation.

Genuine stillness is creative because it restores choice. It returns to the individual the power to act intentionally rather than react mechanically. In its discipline lies the foundation of freedom. To rest rightly is to reclaim sovereignty over one’s mind, to renew the clarity that gives work its purpose. Stillness is not the enemy of progress—it is its conscience.

V. Truth as Rest

Rest and truth are kindred disciplines, each requiring courage—the courage to be still enough to see clearly. In both, one must resist illusion and distraction, standing unflinching before reality. Truth, like rest, is never passive; it is a confrontation, not a retreat. To rest rightly is to cease movement long enough to perceive what is real, to strip away the noise and the comforting falsehoods that make endurance easier but existence hollow. The soul that seeks truth must rest, for truth is not found in haste but in stillness—the stillness of thought sharpened by honesty.

Modern rest, however, is counterfeit. It mimics peace but delivers sedation. We call it “relaxation,” but it is merely distraction—an endless rotation through screens, pleasures, and petty escapes that keep the mind too numb to think. This false peace is not rest but avoidance, a narcotic for the spirit. Entertainment replaces contemplation; consumption substitutes for reflection. The modern man does not rest—he anaesthetises himself against the terror of thought. He fears silence because silence exposes truth, and truth demands change. Comfort has become his creed, and illusion his sanctuary.

To rest in truth, by contrast, is to accept the discomfort of seeing oneself and the world without distortion. It is to sit quietly in the company of reality—its harshness, its beauty, its contradictions—and to say, I will not look away. Such rest does not soothe; it clarifies. It replaces chaos with coherence, indulgence with intention. It demands moral vigilance: the strength to remain still until confusion gives way to understanding. In this sense, rest becomes the act of aligning the inner life with the outer world, a reconciliation between conscience and conduct.

There is profound freedom in such repose. The individual who rests in truth no longer needs distraction or validation. He finds peace not in ignorance but in integrity. His stillness is active, his silence alive. For when one rests in truth, one is no longer escaping the world but engaging it at its most elemental level—through awareness. Rest in this form is not escape from labour but preparation for it, not an end but a beginning. It is the repose of a mind in harmony with reality—the quiet strength of one who has chosen clarity over comfort, and peace over illusion.

VI. The Renewal of Purpose

Rest, when rightly understood, transforms labour. It is not the enemy of work but its purification. When rest becomes reflection, work rises to the level of worship—an offering of mind and will aligned with truth. When rest decays into escape, however, work becomes a form of slavery—an endless repetition of motion devoid of meaning. The individual who never pauses to reflect becomes a servant to habit; the one who rests rightly becomes a creator again. True renewal is not indulgence but reintegration—the rebuilding of vision, the return of clarity, and the reawakening of will.

Both Wesley and Rand, though divided by faith, converge in this truth: that human purpose demands continual renewal. Wesley saw sanctification as an ongoing refinement of the soul—a life spent in the labour of moral becoming. For him, rest was not passive repose but the moment in which conscience was recalibrated, the spirit washed clean of fatigue and vanity. It was the sacred pause where man turned his face once more toward grace and found strength to act rightly. Rand, though she rejected the language of piety, understood the same principle through reason. For her, the mind was the instrument of moral clarity, and rest its maintenance. To think, to re-evaluate, to purge contradictions—these were not luxuries but necessities. Both agreed: a human being cannot act with integrity unless they first think with intention.

Rest is the interval in which that intention is rebuilt. It is the forge in which scattered effort is melted down and reshaped into purpose. In silence, the individual rediscovers direction; in reflection, he transforms fatigue into strength. Ideas take root only in the soil of stillness, where the mind, unhurried and unguarded, allows new insight to emerge. The worker who knows how to rest does not merely resume his labour—he transcends it. His work becomes infused with conscience and creativity; it is no longer mechanical but moral.

The modern world mistakes exhaustion for devotion and rest for indulgence. But to collapse from fatigue is not virtue—it is surrender. Renewal demands control, not escape; engagement, not apathy. Rest is the art of re-entering life with restored power. It is the deliberate act of reuniting thought and action, of ensuring that what one does flows from what one believes.

Without rest, work degenerates into motion without meaning—endless, directionless, and sterile. With it, every act regains intention. In reflection, the worker becomes whole again, his labour no longer an obligation but an affirmation of life. Proper rest does not remove him from the world; it returns him to it, with clearer eyes and a steadier will. To rest is to remember why one works—and in that remembrance lies the true renewal of purpose.

VII. Conclusion – The Sacred Economy of Work and Rest

Work and rest are not opposites—they are twin disciplines bound by the same moral law. Each demands integrity; each, when corrupted, becomes idolatry. Rest without purpose decays into indulgence, while work without reflection becomes worship of motion for its own sake. The rhythm of a meaningful life depends on the balance between them: effort and renewal, action and contemplation, achievement and humility.

Both are sacred because both require mastery of the self. Work disciplines the body and will; rest disciplines the mind and conscience. To labour rightly is to give form to truth; to rest rightly is to recover it. In this balance lies freedom—the power to act with clarity, not compulsion. The individual who understands this rhythm no longer labours for approval or collapses from fatigue. He works with purpose because he knows how to stop; he rests with peace because he knows he will rise again.

This is the “Sabbath mind”—a state not of withdrawal but of transcendence. It is the calm strength of one who steps above the chaos of demand and regains perspective. In stillness, the worker becomes the creator once more, seeing his labour not as burden but as expression. The Sabbath mind rests not to flee the world but to rise above it, to look upon one’s work with honesty and gratitude before beginning anew.

To rest rightly is to prepare to create. To reflect is to renew truth. To be still is to honour the work yet to be done. The sacred economy of work and rest is not measured in hours or wages but in integrity—in the unity of thought, will, and purpose. Through this rhythm, the soul remains whole, and creation, once again, becomes an act of worship.

#rest (in a funny way)

by Elisabeth Mulroy

interesting to consider if my helpless tendency to reflect from all angles i can manage to notice and step into might be what helps to keep me going, even if it sometimes means to keep trying through paralysis of some sort.