The Third Entry: How Cryptography Could Fix the Weakest Link in Accounting

Double-entry bookkeeping has survived for 500 years. Its evidence layer hasn’t kept up. Here’s a mechanism that changes that — without sacrificing privacy.

Every year, companies spend billions on reconciliation. Auditors fly around the world to inspect paper trails. Banks maintain enormous back offices whose entire purpose is to confirm that what Party A says happened is the same as what Party B says happened.

And yet the underlying problem is almost embarrassingly simple: accounting evidence is mutable. An invoice is a file on someone’s computer. A remittance advice is an email. A bank statement is a PDF. Any of these can be altered, fabricated, lost, or simply disputed. The ledger records economic events beautifully — equal and offsetting debits and credits, balanced by structural necessity — but the proof that those events actually occurred the way both parties claim? That proof lives outside the ledger, in a fragile ecosystem of bilateral documents that haven’t fundamentally changed since the Medici.

This is the gap that triple-entry accounting promises to fill. And in a new paper I’ve just submitted to the Journal of Information Systems, I describe — at the mechanism level — exactly how.

The Idea in One Sentence

Every bilateral transaction generates a third entry: a cryptographically committed receipt, recorded on an immutable public medium, that mathematically binds the seller’s invoice to the buyer’s payment. Neither party can subsequently alter what was agreed or deny what was paid, and no unauthorised observer can read the business detail.

That’s it. The rest is making it precise enough to actually work.

What’s Wrong with the Status Quo

Double-entry bookkeeping is one of civilisation’s great inventions. Luca Pacioli described it in 1494, and the core structure — every debit has an equal credit — hasn’t needed revision since. But Pacioli’s system records events; it doesn’t secure evidence. The evidence layer — invoices, purchase orders, receipts, confirmations — is an entirely separate system, maintained bilaterally, and vulnerable to all the things bilateral systems are vulnerable to.

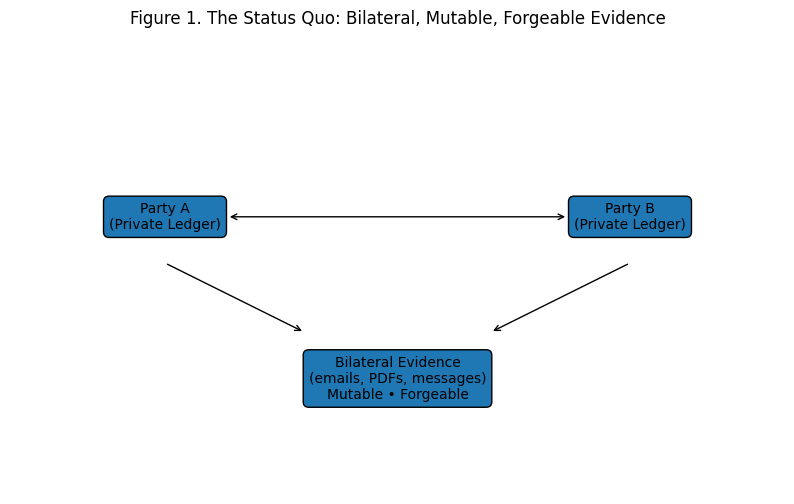

Figure 1. The status quo: each party keeps their own records. The evidence connecting them is bilateral, mutable, and forgeable.

Auditors deal with this by sampling: Double-entry bookkeeping has survived for 500 years. Its evidence layer hasn’t kept up. Here’s a mechanism that changes that — without sacrificing privacy.they pick a subset of transactions, request source documents from both sides, and check for consistency. It works — most of the time — but it’s labour-intensive, exception-driven, and structurally limited. You can never audit every transaction. And when something goes wrong — fraud, disputes, regulatory inquiries — the evidence trail is exactly as strong as the weakest filing cabinet in the chain.

The core problem: The ledger is structurally sound (debits = credits). But the evidence supporting the ledger is bilateral, mutable, and verifiable only through expensive reconciliation.

Enter the Third Entry

The concept of a third entry goes back to Yuji Ijiri’s 1986 proposal for “momentum accounting” and was reframed cryptographically by Ian Grigg in 2005. The idea: for every bilateral transaction, create a third record that lives on a medium neither party controls. This record doesn’t replace the two private ledger entries; it anchors them to something objective, timestamped, and tamper-evident.

The concept is elegant. But the concept alone isn’t enough. You need to answer the hard questions:

How do you link an invoice to its payment in a way that’s provable between the parties but invisible to outsiders?

How do you preserve privacy? The public record can’t leak pricing, volumes, or counterparty identity to competitors.

How do you handle the messy reality of partial payments, overpayments, credits, and netting?

How does an auditor actually use this? What do they see, what do they verify, and what stays hidden?

The paper provides concrete, formally specified answers to each of these. Here’s how.

The Mechanism: Keys, Shared Secrets, and Binding Tags

Step 1: Each party gets a key hierarchy

Every entity has a long-lived master key that never appears on the public record. From this master key, they derive a fresh subkey for every transaction — like peeling off a new ticket from a roll. The derivation is deterministic (the entity can always re-derive any subkey) but one-way (an observer who sees a subkey can’t work backwards to the master key or link it to any other subkey).

This gives you pseudonymity by default: every transaction looks like it involves a different party. But when an auditor needs to confirm that “these 47 invoices all belong to Entity A,” the entity can prove it — by showing that all 47 subkeys derive from the same master key, without revealing the master key itself. The paper specifies two concrete mechanisms for this: a zero-knowledge Schnorr proof (maximum privacy) and a simpler master-key attestation (easier to implement, slightly less private). Each comes with an explicit disclosure model: what the auditor learns, what remains hidden, and what replay protections prevent the proof from being reused across engagements.

Step 2: The two parties create a shared secret

When Party A issues an invoice to Party B, they perform an Elliptic-Curve Diffie–Hellman (ECDH) key exchange. The result is a shared secret — a value that both parties can compute independently, but that no observer can derive from the public keys alone. This is the same mathematics that secures every HTTPS connection on the internet.

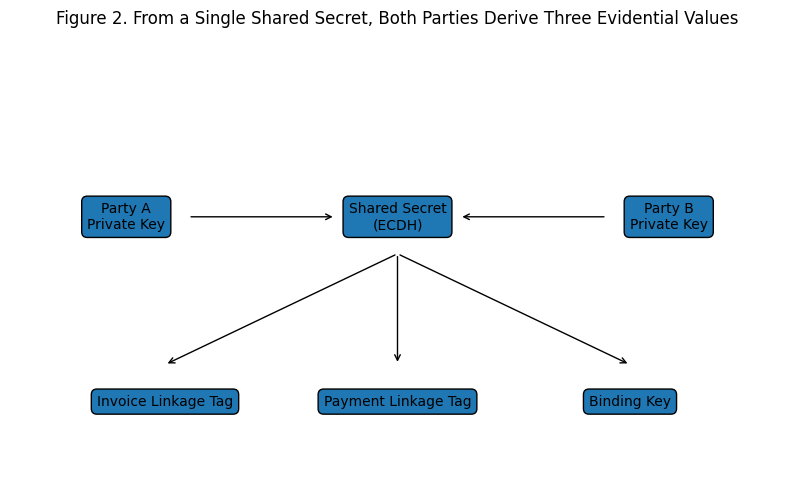

From this shared secret, both parties derive three things:

Figure 2. From a single shared secret, both parties derive three values: an invoice linkage tag, a payment linkage tag, and a binding key. Each serves a different evidential purpose.

The invoice linkage tag identifies the invoice on the public record. The payment linkage tag identifies the corresponding payment — and because both derive from the same secret, the link between them is mathematically provable to the two parties (and to anyone they choose to share the secret with) but invisible to everyone else.

Step 3: Binding tags — the privacy layer

Here’s the subtle part. The invoice note that gets published to the public medium doesn’t contain the actual invoice amount, currency, due date, or tax breakdown in plaintext. Instead, it contains binding tags: cryptographic fingerprints of each field, computed using the shared binding key.

Think of it like sealing each field in a tamper-evident envelope. The public record shows that the envelopes exist and when they were sealed. But only someone with the key can open them.

The security properties are precise:

Computational binding — you can’t find a different value that produces the same tag. This means amounts, dates, and terms can’t be retroactively altered.

Pre-image resistance — you can’t reverse-engineer the value from the tag. Business detail stays private from unauthorised observers.

Selective disclosure — either party can “open” a tag for an auditor by revealing the key and the value. The auditor recomputes the tag, checks it matches the public record, and is satisfied. Auditors verify exactly what they need — no blanket access required.

This is the critical insight: the public record stores evidence, not information. The immutable public medium proves that something happened, when it happened, and that both parties agreed. The details of what happened are revealed only to authorised verifiers, one field at a time.

The Full Picture

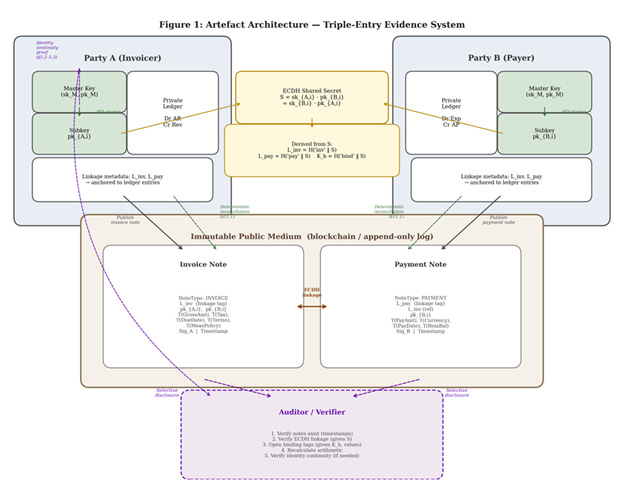

When you put the key hierarchy, the ECDH linkage, and the binding tags together, you get the complete architecture:

Figure 3. The full artefact architecture. Party A publishes an invoice note; Party B publishes a payment note. Both are linked through ECDH-derived tags and anchored on the immutable public medium. Auditors receive selective disclosure — field-level access, not blanket visibility.

The system produces two types of notes for each transaction. An invoice note, published by the seller, contains the invoice linkage tag, both parties’ one-time public keys, binding tags over the gross amount, tax breakdown, due date, settlement terms, and measurement policy (rounding rules, discount schedules), along with the seller’s digital signature and an immutable timestamp. A payment note, published by the buyer, contains the payment linkage tag, a reference to the invoice tag, binding tags over the payment amount, currency, date, and remaining balance, with the buyer’s signature and timestamp.

The linkage tags tie the two notes together. The binding tags lock the business detail. The signatures make each note non-repudiable. The timestamps make the sequence objective. And the whole thing takes about 720 bytes — roughly the size of a single tweet.

A mid-sized company processing 50,000 invoices per month would generate about 36 megabytes of note data. The cryptographic operations for the entire month take less than one minute on a single processor thread. The bottleneck in any real deployment will be the public medium’s throughput and cost, not the cryptography.

How an Auditor Actually Uses This

This is where the paper departs from most blockchain-and-accounting literature, which tends to stop at “it’s immutable” and wave its hands. The paper specifies a concrete five-step verification protocol:

Step 1 — Existence. Does the invoice note exist on the public record at a timestamp consistent with the claimed transaction date?

Step 2 — Linkage. Does a payment note reference this invoice? Is it timestamped later? Do the linkage tags derive from the same ECDH context?

Step 3 — ECDH verification. Both parties disclose the shared secret S to the auditor. The auditor recomputes the linkage tags and confirms they match the public record.

Step 4 — Opening and arithmetic. The auditor opens the binding tags for the fields relevant to the engagement (say, gross amount, tax, and payment amount), verifies each tag against the public record, and checks the arithmetic: gross minus payments equals remaining balance.

Step 5 — Identity continuity (if needed). If the auditor needs to confirm that a set of pseudonymous subkeys all belong to the same entity, the entity provides an identity continuity proof — scoped to that specific engagement, with anti-replay controls that prevent it being reused elsewhere.

The paper includes a full worked example of this disclosure protocol. Imagine an audit engagement where the auditor needs to confirm that three pseudonymous subkeys — used across three invoices issued over six months — all belong to the same supplier. The supplier registers its master public key with a challenge–response, then produces attestations binding each subkey to the master key, scoped to that engagement with a sequence counter. The auditor learns that the three keys belong to one entity; the auditor does not learn the master private key, any other subkeys, or any transaction detail from the notes themselves. Anti-replay controls prevent the same attestation from being presented in a different engagement. The attestation is retained as a working paper.

This kind of operational specificity is what separates the mechanism from prior literature. Most blockchain-accounting papers describe what the auditor could do. This one specifies what the auditor receives, step by step, and explicitly states what is and is not revealed.

The crucial point is that this protocol is selective. An auditor checking revenue recognition can verify invoice amounts and dates without learning the identity of the payers. A dispute about payment timing can be resolved by opening the payment date tag alone. You reveal only what the specific audit question requires.

This transforms auditing from sample-based to population-level. Instead of testing 60 transactions out of 50,000 and hoping they’re representative, the auditor can deterministically match every private ledger entry against its public counterpart. Missing entries are flagged automatically.

Handling the Messy Reality

Textbook transactions — one invoice, one payment, done — are the minority. Real commerce involves partial payments, overpayments, credits, disputes, and netting. The system handles all of them through a consistent mechanism.

Partial payments. Each payment note includes a binding tag over the remaining balance. The arithmetic chain is verifiable: gross amount minus the sum of all payments must equal the final remaining balance. Every step is independently checkable.

Overpayments. A payment that exceeds the balance produces a negative remaining balance, triggering a credit note — essentially an invoice in reverse, linked to the original context. The credit can be settled independently or netted against future invoices.

Netting. A netting note references the full set of invoice tags being netted and commits to the net amount. Both parties sign. The arithmetic is verifiable: the net must equal the algebraic sum of outstanding balances on all referenced invoices and credits.

In every case, the principle is the same: the public record contains the binding tags and linkage; the arithmetic is verified by opening those tags when needed. No special cases, no trust assumptions beyond the cryptography itself.

What This Maps To in Audit Doctrine

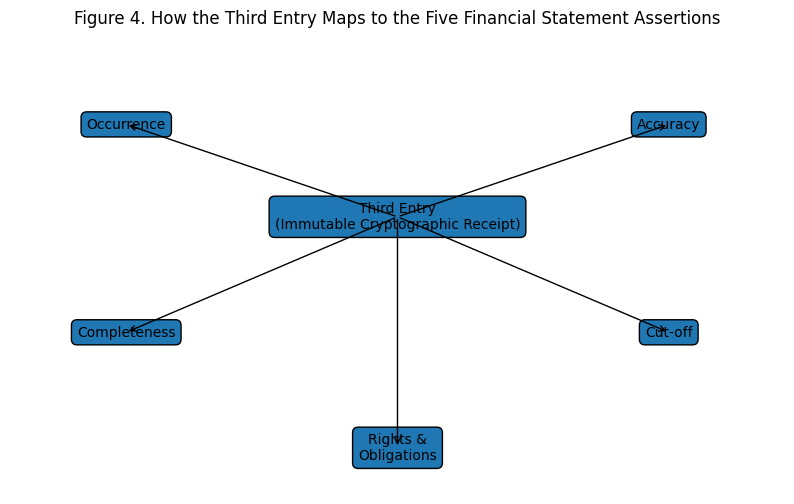

The paper evaluates the mechanism against the five financial statement assertions that auditing standards (ISA 315, AU-C 315) require evidence for. This is where it meets the real world:

Figure 4. How the third entry maps to the five financial statement assertions. The improvement is structural, not marginal.

The improvement is not incremental. The third entry doesn’t make existing evidence slightly better; it introduces a new class of evidence that is independently verifiable, immutable, and mathematically bound to the counterparty relationship. An auditor using this system doesn’t rely on management representations or bilateral confirmations for any of the five assertions — they verify against an immutable public record using deterministic mathematics.

Take completeness as an example. Today, an auditor tests completeness by sending confirmation letters to a sample of counterparties and waiting weeks for responses. The response rate is typically incomplete, and non-responses require alternative procedures. With the third entry, the auditor queries the public medium for all notes linked to the entity’s subkeys, matches them against the private ledger, and any unmatched entries — in either direction — are flagged immediately. No sampling. No confirmation letters. No waiting. Population-level completeness assurance, produced deterministically in minutes.

Or consider cut-off — one of the most common areas of audit adjustment. Period-end revenue manipulation typically involves backdating or advancing invoices across the reporting boundary. With an immutable timestamp on the public medium, the question becomes trivially verifiable: either the note was recorded before the cut-off or it wasn’t. There is no judgment call, no inspection of postmarks, no reliance on client representations about “when the goods were shipped.”

The Security Argument

Most papers in this space assert security through proximity to blockchain. “It’s on a blockchain, therefore it’s secure” is the implicit claim. That’s not good enough.

The paper includes an end-to-end security argument: five formal propositions, each reducing a claimed accounting property to a specific cryptographic assumption:

Proposition 1 — Invoice non-repudiation follows from the digital signature scheme’s unforgeability and the public medium’s immutability.

Proposition 2 — Binding tag integrity follows from the collision resistance of the hash function.

Proposition 3 — Bilateral confidentiality follows from the pre-image resistance of the hash function and the Computational Diffie–Hellman assumption.

Proposition 4 — Invoice–payment linkage integrity follows from the CDH assumption: only the holder of the buyer’s private key can produce the correct payment linkage tag.

Proposition 5 — Selective disclosure correctness follows from the determinism of the hash function and the uniqueness of field labels.

Each assumption is named. Each proposition is stated with a proof sketch. The argument is explicitly not a full simulation-based proof — that would be overkill for an accounting journal and the wrong frame for the contribution. It is a rigorous semi-formal reduction that shows exactly where each assumption is load-bearing, and what breaks if it fails.

A reference prototype confirms the practical feasibility: a full invoice–payment cycle takes 1.2 milliseconds on commodity hardware. A single thread handles 72 million transaction cycles per day. The bottleneck will never be the cryptography.

What This Is — and What It Isn’t

A boundary statement matters here, because the blockchain-adjacent space is full of overclaiming.

This is not a blockchain paper. The mechanism is agnostic to the specific public medium. It works on Ethereum, on Hyperledger Fabric, on a notarised append-only log, or on any system that provides immutability and reliable timestamping. The paper specifies the accounting evidence layer, not the infrastructure layer.

This is not a claim about legal finality. The mechanism provides technical non-repudiation: under standard cryptographic assumptions, neither party can alter, deny, or fabricate a recorded transaction. Whether a binding tag constitutes admissible evidence in a court of law depends on the applicable jurisdiction — eIDAS in Europe, ESIGN/UETA in the United States, and so on. The mechanism is compatible with these frameworks but doesn’t presuppose any particular one.

This is not speculation. There is a working prototype, a formally specified security argument, an evaluation against the actual doctrines that govern audit and assurance, and worked examples covering every major commercial transaction type.

The core contribution is not the cryptographic primitives — ECDH, hash functions, digital signatures are all decades old. It’s their systematic integration into an accounting evidence framework with formally characterised properties, evaluated against the doctrines that actually govern audit and assurance.

Why Now — and Who Goes First

The intellectual ingredients have existed for years. Ijiri proposed the third dimension in 1986. Grigg described the cryptographic receipt in 2005. ECDH dates to the 1970s. Hierarchical deterministic keys were standardised in 2012. So why hasn’t this been built?

Part of the answer is that the infrastructure wasn’t ready. You need an immutable, timestamped public medium — and until relatively recently, the options were either impractical (trusted notary services with single points of failure) or non-existent. The maturation of blockchain technology, and more broadly the emergence of append-only verifiable data structures in enterprise infrastructure, has changed this. Immutable public media are now commodity infrastructure, whether you use Ethereum, Hyperledger Fabric, or a cloud-native append-only log service.

But I think the bigger reason is that the accounting and cryptography communities haven’t been talking to each other at the right level of specificity. The cryptographers build beautiful primitives but don’t know what “occurrence assertion” means. The accountants know exactly what audit evidence needs to do but don’t know what an ECDH shared secret is. The paper is an explicit attempt to bridge that gap: to take established cryptographic mechanisms and wire them together in a way that maps precisely onto established audit doctrine.

What has also changed is the demand side. The push toward continuous assurance, real-time reporting, and inter-organisational trust is accelerating. Regulators want more transparency. Auditors want better evidence. Companies want cheaper reconciliation. And the economics of the mechanism are compelling: a mid-sized enterprise’s entire monthly cryptographic overhead is under one minute of compute time and 36 megabytes of storage.

Critically, you don’t need universal adoption. The benefits accrue at the dyad level, from the very first transaction between two participating parties. This is how electronic data interchange (EDI) diffused in the 1990s: not through simultaneous industry-wide adoption, but through bilateral hub-and-spoke deployment along existing trading relationships. The first adopters will be organisations with high-value, high-frequency bilateral relationships where reconciliation cost and dispute risk are highest: a supplier and its largest customer, a bank and its correspondent, an insurer and its reinsurer. Auditor demand may itself be a catalyst — if an audit firm begins requesting cryptographic evidence from clients, those clients have a direct incentive to implement the mechanism with their key counterparties.

The mechanism pays for itself at the first dyad.

Where To Go From Here

The paper is being submitted to the Journal of Information Systems (American Accounting Association). It’s framed as a design science artefact — a formally specified method for producing immutable accounting evidence — evaluated against financial statement assertions, a threat-model-to-control mapping, design science research criteria, and a benchmarked prototype.

What comes next is implementation, deployment, and — most importantly — the interdisciplinary work at the boundary between cryptographic evidence and legal recognition. The mechanism provides the technical foundation. The legal, regulatory, and institutional superstructure still needs to be built. Questions like “does a binding tag constitute admissible evidence under English law?” and “how should PCAOB standards accommodate cryptographic verification procedures?” are not questions this paper answers. They are questions this paper makes it possible to ask precisely, because for the first time there is a concrete mechanism to point at.

There is also a research agenda here. The current mechanism uses keyed-hash tags, which provide binding and hiding but not algebraic homomorphism — meaning you can verify individual values but not compute population-level sums without opening every tag. Extending the scheme with Pedersen commitments or compact range proofs would enable an auditor to verify that total revenue equals the sum of all invoice amounts without seeing any individual amount. That’s the next frontier: population-level assurance with zero individual disclosure.

But the core architectural question — can we make accounting evidence immutable, bilaterally verifiable, and privacy-preserving without breaking the existing framework? — has, I believe, a clear answer now.

Yes. And here’s exactly how.

The full paper, “Triple-Entry Accounting with Deterministic Invoice–Payment Linkage, Hierarchical Keys, and Verifiable Private Disclosure,” is available from the author. Contact: cw881@exeter.ac.uk

Craig Wright is at the University of Exeter. Aspects of the methodeology described herein are the subject of a patent or patent application.